Human Factors Engineering for Medical Devices: Complete FDA Usability Guide

- Beng Ee Lim

- Dec 17, 2025

- 9 min read

Human Factors Engineering (HFE), also called usability engineering, is how FDA expects you to show that intended users can operate your device safely and effectively in the intended use environment, especially when use error could cause harm. For many higher-risk device types, FDA often expects human factors data in 510(k)s and PMAs, and it is common to see it in De Novo programs when the user interface drives risk. If you change a user interface in a way that can affect comprehension or use, you may need additional human factors evidence and possibly a new submission. Cost and timeline vary widely, but a focused HFE program often runs from tens of thousands of dollars to over $100,000 depending on complexity, recruiting, and the number of users and scenarios you must cover. This guide walks you through FDA’s HFE expectations, the December 2022 draft guidance on what HFE information to include in marketing submissions, validation testing essentials, and common documentation gaps that trigger FDA questions and postmarket risk.

What is Human Factors Engineering and Why FDA Cares

Human Factors Engineering (HFE), sometimes referred to as usability engineering, applies knowledge about human behavior, abilities, and limitations to medical device design. The goal is to ensure devices can be used safely and effectively by intended users in real-world environments, without preventable use errors.

FDA’s 2016 Human Factors guidance defines HFE as the application of human behavior knowledge to device design, including software, systems, and tasks, to achieve adequate usability. FDA expects human factors evidence when use error could lead to patient harm, especially for higher-risk devices and user-interface-driven technologies.

FDA focuses on HFE because many device problems do not come from mechanical failure, but from how devices are actually used under real clinical conditions, time pressure, distractions, fatigue, alarms, and imperfect lighting. When design does not account for these realities, use errors become more likely.

HFE evaluates three core elements:

Users: Intended operators, their training, and physical or cognitive limitations

Use environments: Hospitals, home care, ambulances, and other real settings

User interface: Displays, controls, labels, alarms, instructions, and training

When these elements do not align, use errors occur. HFE is the structured process FDA relies on to identify and reduce these risks before devices reach patients.

When is Human Factors Engineering Required for Your Device?

FDA’s design validation regulation (21 CFR 820.30(g)) expects manufacturers to ensure devices meet defined user needs in actual or simulated use conditions, including how real users interact with device interfaces. Human factors evidence is commonly submitted during premarket reviews when use-related risk could lead to serious harm.

In practice, FDA’s risk-based human factors framework, reflected in the December 2022 draft guidance (Content of Human Factors Information in Medical Device Submissions), helps determine how much HFE documentation is appropriate. The framework guides decisions based on whether the device is modified, whether user interface changes affect use, and whether critical tasks or new use-related hazards exist.

Practical Risk Categories (Industry Interpretation)

Category 1: Minimal HFE Documentation

Brief summary showing no meaningful UI change or use-related risk

Applies to backend software updates, minor labeling tweaks with no UI impact

No validation testing typically required

Category 2: Moderate HFE Documentation

Use-related risk analysis summary

Early analyses (task analysis, risk controls) and formative evaluation results

Discussion of risk controls and residual risk

Validation testing may not be required if justified

Category 3: Full HFE Documentation

All Category 2 elements

Detailed description of critical tasks and risk-related use scenarios

Human factors validation protocol and full report

Capture of use errors, close calls, and mitigations

Many FDA reviewers expect evidence from usability validation studies with adequate participant diversity per user group (consistent with industry standards such as ISO 62366-1)

Devices with tasks whose failure could cause serious harm will often fall in Category 3 during 510(k) review if the use interface drives risk.

Devices with High Human Factors Expectations

FDA historically prioritizes thorough human factors evaluation for devices where use error risk is elevated, including:

Home-use and lay-user devices

Combination drug-device products (e.g., auto-injectors)

Infusion pumps and large volume delivery systems

Insulin pumps and other diabetes management hardware

Emergency and defibrillator interfaces

Surgical robots and complex capital equipment

Software with complex workflows

If you’re unsure which category applies or how much evidence FDA will expect, submit a Pre-Submission request through FDA’s official program to get early feedback.

The HFE Process: FDA’s 5-Step Framework

FDA’s 2016 Human Factors guidance describes a structured usability engineering process that should be integrated throughout device development, not added at the end. The purpose is to identify and mitigate use-related risks before a device reaches patients.

Step 1: Define Users, Use Environments, and the User Interface

Manufacturers must clearly define all intended user groups, including primary users (clinicians, patients) and secondary users (biomedical engineers, IT staff), and account for variability in experience, physical ability, literacy, and training.

FDA also expects characterization of real use environments, including physical conditions (lighting, noise, space), workflow pressures (interruptions, multitasking), and organizational factors (handoffs, emergency protocols).

The user interface must be defined comprehensively, including hardware controls, displays, alarms, labeling, packaging, and training materials. This information forms the foundation for identifying critical tasks and use-related hazards.

Step 2: Identify Use-Related Hazards and Critical Tasks

A critical task is a user action which, if performed incorrectly or not performed at all, could result in serious harm to the patient or user, including death, permanent impairment, or the need for medical intervention.

Critical tasks are typically identified through task analysis, use-related risk analysis (such as FMEA), review of predicate device complaints and MAUDE adverse events, and expert human factors review. FDA expects manufacturers to document the methodology used to identify critical tasks, not just the final list.

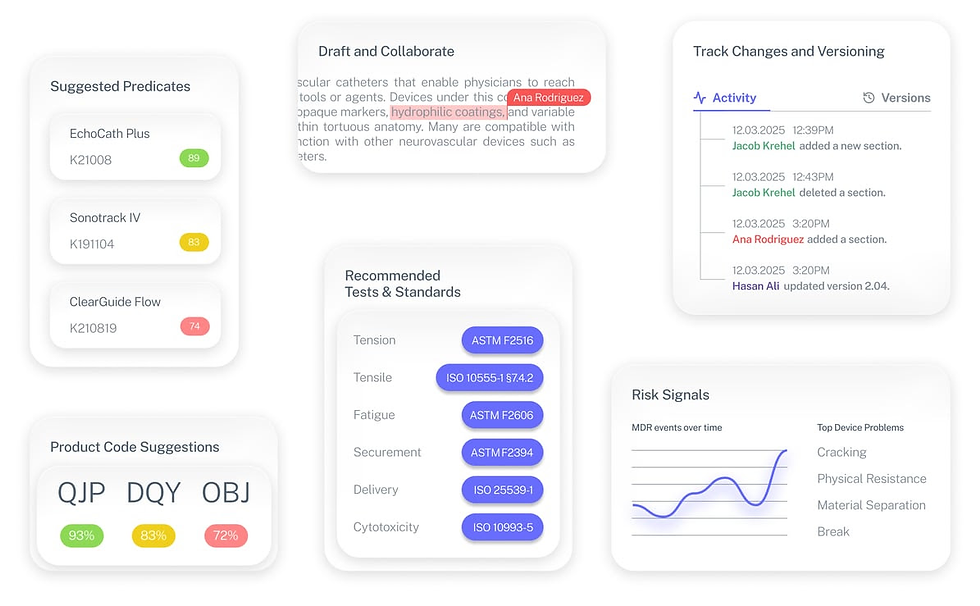

Tools like Complizen help teams centralize user profiles, critical task rationale, and use-related risk evidence (including predicate issues and MAUDE data), so HFE decisions remain consistent and defensible across development and submission.

Step 3: Conduct Preliminary Analyses and Formative Evaluations

Formative evaluations are conducted early and iteratively to uncover usability issues while design changes are still feasible. These may include heuristic evaluations, cognitive walkthroughs, and formative usability testing with representative users.

While raw formative data is not submitted to FDA, manufacturers are expected to summarize key findings and describe how results informed design decisions in the human factors report.

Step 4: Implement Risk Control Measures

FDA follows a hierarchy of risk control, prioritizing inherently safe design first, followed by protective measures, and lastly information for safety such as warnings and training.

FDA has been explicit that training alone is not an adequate control for critical tasks, and warnings must be shown to be effective through validation testing.

Step 5: Conduct Human Factors Validation Testing

Human factors validation testing demonstrates that intended users can perform critical tasks safely and effectively in realistic use conditions. FDA does not mandate a fixed sample size, but expects enough participants per user group to reasonably capture use-related risk, often guided by device complexity and severity of harm.

Validation testing must evaluate all critical tasks, capture use errors and close calls, and assess whether risk controls are effective. If serious use errors occur, manufacturers are expected to investigate root cause, implement design changes, and re-evaluate. FDA may accept residual use-related risk only when justified through a robust benefit-risk analysis.

Common HFE Validation Failures and How to Avoid Them

Based on FDA feedback and industry experience, these are common human factors validation mistakes that lead to FDA objections, additional information requests, or delayed clearance.

Failure #1: Recruiting the Wrong Participants

Problem: Participants do not represent the intended user population.

Examples:

Testing hospital devices with medical students instead of practicing clinicians

Testing home-use devices with highly educated early adopters rather than typical patients

Narrow age ranges that don’t reflect real users

Recruiting non-U.S. users without considering differences in training or healthcare systems

How to Avoid It:

Define detailed user profiles before recruitment

Screen participants against objective inclusion criteria

Document how participants represent intended users

Include a realistic range of experience, age, and abilities

Failure #2: Unrealistic Test Environments

Problem: Testing conditions do not reflect actual use.

Examples:

Quiet lab testing for devices used in chaotic emergency settings

Single-task testing when real use involves multitasking

Validation testing with non-production-representative units

How to Avoid It:

Study real workflows through contextual inquiry

Simulate realistic noise, lighting, interruptions, and time pressure

Use production-equivalent devices for validation testing

Failure #3: Inadequate Test Protocols

Problem: Validation testing fails to assess critical tasks.

Examples:

Testing only “ideal” use paths

Coaching participants during tasks

Ignoring edge cases where errors are most likely

How to Avoid It:

Map every critical task to realistic test scenarios

Use representative patient cases and workflows

Include error and recovery scenarios

Use actual labeling, IFU, and training materials

Failure #4: Poor Data Analysis

Problem: Results do not meet FDA expectations.

Examples:

Reporting task success rates without root cause analysis

Blaming users for errors

Ignoring close calls and repeated difficulties

How to Avoid It:

Perform root cause analysis for every use issue

Identify design contributors to errors

Look for patterns across participants

Treat user errors as design feedback, not user failure

Tools like Complizen help teams centralize use-error observations, root cause analyses, and related evidence, including predicate issues and MAUDE data, so HFE conclusions are traceable and defensible when FDA reviews the submission.

Failure #5: Testing Too Late

Problem: Validation reveals issues after design is locked.

Examples:

No formative testing during development

Discovering critical tasks were not tested

Finding labeling or alarms ineffective after finalization

How to Avoid It:

Conduct formative testing early and iteratively

Integrate HFE timelines into overall development plans

Consider a Pre-Submission to align on validation approach before final testing

HFE Cost and Timeline: A Reality Check

Human factors engineering is not free, and it is not fast. For many Class II devices submitted through the 510(k) pathway, HFE costs commonly fall in the tens of thousands of dollars, with timelines spanning several months. The exact scope depends on device complexity, number of user groups, and use-related risk.

Typical Industry Cost Ranges (Class II Devices)

Formative Testing (iterative):

Commonly spans multiple rounds during development

Often ranges from $15K–$30K, depending on number of users, prototypes, and testing depth

Human Factors Validation Testing:

Frequently the largest cost driver

Often ranges from $30K–$70K, depending on user groups, test environment, and protocol complexity

External HFE Consultant Support (if used):

Protocol development, moderation, and reporting

Commonly $20K–$50K, but varies widely by vendor and scope

For a typical Class II device with multiple user groups, the total HFE effort often lands around $50K–$100K, though simpler devices may cost less and complex systems may exceed this range.

Typical Timeline (Overlapping with Development)

Formative testing: 3–6 months (iterative, during design)

Validation protocol development and Pre-Submission (if used): ~1–2 months

Participant recruitment: ~1–2 months

Validation testing execution: ~2–4 weeks

Analysis and reporting: ~1–2 months

End-to-end, many teams spend 6–12 months from early formative testing through a final validation report. These activities typically run in parallel with device development, not after it.

The key takeaway: HFE cannot be bolted on at the end. FDA expects it to be integrated into the design process, with decisions and iterations clearly documented along the way.

This is where teams often underestimate effort. Keeping user assumptions, formative findings, critical tasks, and validation rationale organized throughout development makes timelines more predictable and avoids late-stage surprises during FDA review.

The HFE Submission: What Goes in Your 510(k)

For many 510(k)s involving critical tasks, FDA expects a human factors report that clearly demonstrates how use-related risks were identified, mitigated, and validated. While FDA does not prescribe a mandatory section-by-section format, comprehensive HFE submissions typically follow a structure like the one below.

Core Sections FDA Expects to See

1. Device Description and Use Context

Intended users and relevant characteristics

Use environments and contextual factors

User interface elements

Intended use and indications

2. Preliminary Analyses

Methods used (task analysis, use-related risk analysis, expert review)

Known use problems from predicate devices

User research findings

3. Use-Related Risk Analysis

Process for identifying critical tasks

Severity assessment approach (often aligned with ISO 14971)

Complete list of critical tasks and use scenarios

Justification for any critical tasks not evaluated

4. Risk Control Measures

Design features and protective measures

Alarms, confirmations, forcing functions

Labeling and training elements

Application of risk control hierarchy

5. Formative Evaluation Summary

Number of rounds conducted

Key findings and design changes

How testing informed design evolution

6. Validation Testing Details

Objectives and protocol overview

Participant selection and demographics

Test environment and training provided

Tasks and scenarios evaluated

Data collection methods

7. Validation Results

Use errors, close calls, and difficulties

Root cause analysis and patterns

Design changes and residual risk justification

8. Conclusions

Summary of findings

Statement supporting safe and effective use

Remaining limitations or cautions

Appendices may include protocols, scripts, training materials, and summarized data as appropriate.

What FDA Reviewers Focus On

During review, FDA commonly asks:

Were all critical tasks evaluated?

Were participants truly representative?

Did testing reflect realistic use conditions?

Were use errors analyzed rigorously?

Are residual risks adequately justified?

In practice, compiling this evidence across multiple documents is where teams lose time and consistency. Using a structured regulatory workspace, such as Complizen, helps keep user profiles, critical task rationale, predicate issues, and validation evidence aligned with FDA expectations and easy to reference during review.

The Fastest Path to Market

No more guesswork. Move from research to a defendable FDA strategy, faster. Backed by FDA sources. Teams report 12 hours saved weekly.

FDA Product Code Finder, find your code in minutes.

510(k) Predicate Intelligence, see likely predicates with 510(k) links.

Risk and Recalls, scan MAUDE and recall patterns.

FDA Tests and Standards, map required tests from your code.

Regulatory Strategy Workspace, pull it into a defendable plan.

👉 Start free at complizen.ai