What Is Substantial Equivalence (SE) in FDA 510(k)? Definition & Criteria

- Beng Ee Lim

- Jul 4, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 7, 2025

In 510(k), substantial equivalence (SE) means your device has the same intended use as a predicate and either the same tech characteristics or different ones that don’t raise new questions of safety or effectiveness—with data to support that conclusion. FDA applies this SE test per FD&C §513(i) and its 510(k) SE guidance.

This guide covers substantial equivalence criteria, predicate selection strategy, and how to build winning SE arguments.

The Substantial Equivalence Framework

FDA's Two-Step Evaluation Process

Step 1: Intended Use Comparison

FDA first determines whether your device and predicate have identical intended use. This includes indications for use, patient population, and general device purpose. Different intended use = automatic NSE (not substantially equivalent).

Step 2: Technological Characteristics Analysis

If intended use matches, FDA evaluates whether technological differences raise new questions of safety or effectiveness requiring additional controls or testing.

The SE Decision Tree

Same Intended Use + Same Technology = SE

When devices have identical intended use and technological characteristics, substantial equivalence is straightforward.

Same Intended Use + Different Technology = Maybe SE

FDA evaluates whether technological differences raise new safety or effectiveness questions. Performance data can demonstrate that differences don't affect safety or effectiveness.

Different Intended Use = NSE

No amount of performance data can overcome different intended use. You need a different predicate or different regulatory pathway.

What "Substantial Equivalence" Actually Means

NOT Required:

Identical devices (differences are expected)

Same manufacturer or design approach

Equivalent performance in all parameters

Same materials or components

Required:

Same intended use and indications

Either same technology OR different technology that doesn't raise new questions

Performance data supporting safety and effectiveness claims

Compliance with applicable standards and controls

Intended Use: The Make-or-Break Factor

Defining Intended Use

FDA's Definition: "The general purpose of the device or its function," including indications for use, patient population, and clinical application.

Key Components:

Indications for use: Specific diseases, conditions, or purposes

Patient population: Age, condition, anatomical location

Clinical setting: Hospital, home use, physician office

Device purpose: Diagnostic, therapeutic, monitoring

Common Intended Use Mistakes

Too Broad Intended Use Claiming broader indications than your predicate supports requires additional clinical evidence and potentially different regulatory pathway.

Patient Population Mismatch Pediatric vs. adult populations, specific disease stages, or anatomical differences can constitute different intended use.

Clinical Setting Differences Professional use vs. over-the-counter, hospital vs. home use, or emergency vs. routine applications may require different predicates.

Intended Use Strategy

Match Predicate Exactly: Your indications for use should align precisely with your chosen predicate's cleared indications.

Avoid Indication Creep: Don't expand beyond predicate scope even if clinically logical—save additional indications for future submissions.

Document Rationale: Clearly explain how your intended use matches predicate in terms of purpose, population, and clinical application.

Technological Characteristics: Same or Different?

What Constitutes "Different" Technology

FDA considers technology different when there are significant changes in:

Materials (biocompatibility, mechanical properties)

Design (form factor, mechanism of action)

Energy source (power, delivery method)

Operating principles (algorithm, measurement approach)

Technological Characteristics Analysis

Materials Comparison

Biocompatibility profile and patient contact materials

Mechanical properties affecting device performance

Degradation characteristics for implantable devices

Design Features

Mechanism of action and operating principles

User interface and control methods

Physical configuration and form factor

Performance Specifications

Measurement range, accuracy, and precision

Power requirements and battery life

Software functionality and algorithms

When Different Technology Still Achieves SE

Performance Data Bridges Differences: Clinical or bench testing demonstrates that technological differences don't affect safety or effectiveness.

Established Safety Profile: Different materials or components with well-established biocompatibility and performance history.

Conservative Design Changes: Modifications that improve safety or effectiveness without introducing new risks or questions.

Building Your Substantial Equivalence Argument

Predicate Selection Strategy

Ideal Predicate Characteristics:

Recent clearance (within 5 years) reflects current standards

Same manufacturer may simplify technological comparison

Minimal differences from your device in key characteristics

Strong safety profile with no significant post-market issues

Multiple Predicate Approach: Sometimes using multiple predicates for different device aspects strengthens your SE argument, but ensure all predicates share the same intended use.

Comparison Table Development

Side-by-Side Format: Create comprehensive comparison tables covering all relevant device characteristics.

Highlight Similarities: Emphasize areas where devices are identical or nearly identical in design, materials, and performance.

Address Differences: For each difference, explain why it doesn't raise new safety or effectiveness questions.

Performance Data Integration: Link performance testing directly to technological differences requiring justification.

Common SE Arguments That Fail

Performance Similarity Alone: "Our device performs similarly" without addressing technological differences doesn't support SE.

Feature Enhancement Claims: "Our device is better/safer/more effective" suggests different questions of safety or effectiveness.

Inadequate Difference Analysis: Failing to acknowledge or inadequately addressing technological differences leads to NSE.

Poor Predicate Selection: Choosing convenience predicate rather than most appropriate comparison device weakens SE argument.

Performance Data: Bridging Technological Gaps

When Performance Data Is Required

Different Materials: Biocompatibility testing for new materials or material combinations.

Modified Design: Engineering testing demonstrating equivalent performance despite design changes.

New Technology: Clinical or bench data showing new technology doesn't raise safety or effectiveness questions.

Software Changes: Validation testing for modified algorithms or software functionality.

Types of Supporting Evidence

Bench Testing: Engineering performance, durability, and safety testing according to applicable standards.

Biocompatibility Testing: ISO 10993 testing for devices with patient contact or new materials.

Clinical Data: Human studies when bench testing insufficient to demonstrate substantial equivalence.

Literature Review: Published studies supporting safety and effectiveness of similar technologies.

Performance Data Strategy

Standards Compliance: Meet or exceed applicable consensus standards and special controls.

Predicate Comparison: Demonstrate performance equivalent to or better than predicate device.

Risk Mitigation: Show how any performance differences are mitigated through design or labeling.

Clinical Relevance: Connect bench testing results to clinical performance and patient safety.

NSE Recovery: When Substantial Equivalence Fails

Understanding NSE Determinations

Why NSE Happens:

Intended use doesn't match predicate

Technological differences raise new questions

Insufficient performance data to bridge differences

Inappropriate predicate selection

NSE Response Options

New Predicate Device: Find different predicate with better technological match and same intended use.

Additional Performance Data: Provide clinical or bench testing to address FDA's safety or effectiveness questions.

Modified Intended Use: Narrow indications to match available predicates (if commercially viable).

Alternative Pathway: Consider De Novo if no appropriate predicate exists.

NSE Recovery Strategy

Analyze FDA's Rationale: Understand specific safety or effectiveness questions FDA identified.

Address Root Cause: Don't just add data—address fundamental issue that caused NSE.

Consider Pathway Change: Sometimes De Novo is faster than trying to force inappropriate 510(k).

Engage FDA Early: Pre-submission meeting can clarify SE requirements before resubmission.

Your SE Evaluation Framework

Phase 1: Intended Use Assessment

Compare your device's intended use with potential predicates using FDA's specific criteria for indications, population, and clinical application.

Identify exact matches and document rationale for why intended use is identical.

Flag any differences in patient population, clinical setting, or device purpose that could constitute different intended use.

Phase 2: Technological Analysis

Create detailed comparison of materials, design, energy source, and operating principles.

Categorize differences as identical, similar, or significantly different based on FDA's technological characteristics criteria.

Assess safety/effectiveness impact of each technological difference.

Phase 3: Evidence Strategy

Determine performance data needs based on technological differences requiring justification.

Plan testing strategy using applicable standards and predicate device performance as benchmarks.

Consider clinical evidence for differences that can't be addressed through bench testing alone.

Phase 4: SE Argument Development

Build comprehensive comparison emphasizing similarities and addressing differences systematically.

Integrate performance data directly with technological difference justification.

Prepare for FDA questions about predicate selection and SE rationale.

Substantial Equivalence: Your 510(k) Foundation

Substantial equivalence isn't just a regulatory hurdle—it's the strategic foundation that determines your entire 510(k) approach. Companies that master SE evaluation and predicate selection gain significant advantages through faster clearances and reduced development risk.

Success in substantial equivalence requires thinking like FDA: same intended use is non-negotiable, technological differences must be justified with appropriate evidence, and performance data must directly address safety and effectiveness questions.

The Fastest Path to Market

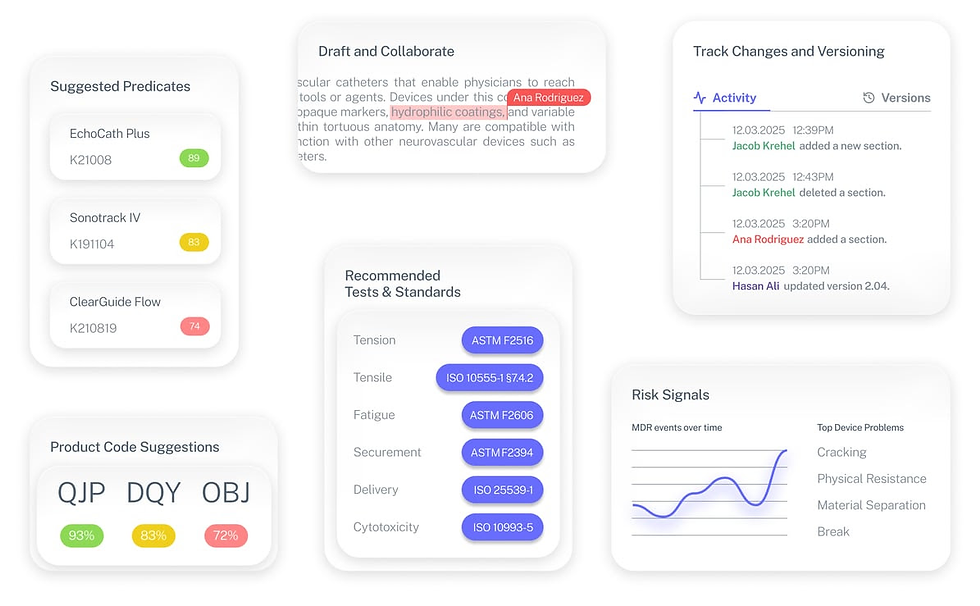

No more guesswork. Move from research to a defendable FDA strategy, faster. Backed by FDA sources. Teams report 12 hours saved weekly.

FDA Product Code Finder, find your code in minutes.

510(k) Predicate Intelligence, see likely predicates with 510(k) links.

Risk and Recalls, scan MAUDE and recall patterns.

FDA Tests and Standards, map required tests from your code.

Regulatory Strategy Workspace, pull it into a defendable plan.

👉 Start free at complizen.ai

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use multiple predicate devices for substantial equivalence?

Yes, but all predicates must have the same intended use as your device. You might reference different predicates for different technological aspects, but the overall SE argument must be coherent and well-justified.

What if there's no perfect predicate match?

Focus on finding the closest predicate with identical intended use, then use performance data to bridge technological differences. If no reasonable predicate exists, consider the De Novo pathway.

How recent should my predicate device be?

While there's no FDA requirement for recent predicates, devices cleared within the last 5 years typically reflect current safety and effectiveness standards, making SE arguments stronger.

Can I claim substantial equivalence to a predicate with known issues?

FDA considers predicate device safety profile in SE determinations. Predicates with significant post-market problems or recalls may not support SE claims.

What happens if FDA disagrees with my predicate selection?

FDA may suggest alternative predicates or request additional data to support your chosen predicate. In some cases, they may determine no appropriate predicate exists, requiring De Novo pathway.