What Happens If FDA Disagrees With Your Predicate Device? Complete Response Guide

- Beng Ee Lim

- Dec 18, 2025

- 9 min read

If FDA disagrees with your predicate choice, you'll get an Additional Information (AI) request or a Not Substantially Equivalent (NSE) determination. AI requests often add months and require either: (1) switching to a different predicate, (2) providing stronger substantial equivalence rationale, or (3) withdrawing and refiling. Not Substantially Equivalent (NSE) determination usually means you must submit new 510(k) with different predicate or pursue De Novo.

This guide walks you through exactly what happens when FDA challenges your predicate choice, your response options with realistic timelines and costs, and—most importantly—how to prevent this situation before you ever submit.

How FDA Signals Predicate Disagreement

FDA typically does not wait until the end of review to raise concerns about your predicate strategy. Instead, reviewers often signal issues incrementally throughout the 510(k) review process, giving you opportunities to clarify or adjust before a final decision.

Signal #1: Additional Information (AI) Request

When it happens: Often during substantive review, after the submission is accepted for review.

What it looks like: FDA may request clarification on intended use alignment, technological differences, or comparative performance data, and may suggest identifying alternative predicates that more closely match your device.

What it means: FDA is not yet convinced that your chosen predicate adequately supports substantial equivalence. An AI request is an opportunity to strengthen your rationale or adjust your predicate strategy.

Timing implications: You generally have up to 180 days to respond. FDA’s review clock is paused during this period, so the overall timeline can extend by weeks or months depending on response quality and review complexity.

Signal #2: Informal Communication During Review

When it happens: At any point during interactive review.

What it looks like: Emails or calls asking targeted questions, such as why a specific predicate was selected, how differences are addressed, or whether you are aware of differences in indications for use.

What it means: These communications are part of FDA’s documented review record. How you respond can influence whether the issue is resolved informally or escalates to a formal AI request.

Response strategy: Treat informal questions seriously. Provide clear, referenced answers and document all communications.

Signal #3: Not Substantially Equivalent (NSE) Determination

When it happens: At the conclusion of FDA’s review.

What it looks like: FDA issues a formal NSE letter stating that differences in intended use, technological characteristics, or supporting data prevent a finding of substantial equivalence.

What it means: The device cannot be marketed under that submission. FDA has determined it is Not Substantially Equivalent to the identified predicate.

Next steps: Depending on FDA feedback, options may include submitting a new 510(k) with a different predicate, pursuing the De Novo classification pathway, or, in some cases, considering a PMA route if risk and novelty warrant it.

Practical Reality

In practice, teams that respond fastest are the ones who have already mapped predicate comparisons, recall history, adverse events, and substantial equivalence rationale before submission. Tools like Complizen help centralize predicate analysis, MAUDE data, and equivalence documentation, making it easier to spot weaknesses early and respond quickly when FDA signals concern.

The 7 Most Common Reasons FDA Challenges Your Predicate Strategy

Based on NSE determinations and FDA review feedback, these are the most common predicate-related issues that prevent a finding of substantial equivalence.

Reason #1: Intended Use Mismatch

The issue: Your device and predicate serve different clinical purposes, even if the designs appear similar.

Why it matters: Intended use is the first and most critical substantial equivalence test. If intended uses differ, FDA cannot find substantial equivalence, regardless of technological similarity.

Key nuance:

Intended use includes:

Anatomical site

Patient population

Clinical purpose

Use environment

Even small wording differences can imply different risk profiles.

Reason #2: Technological Differences That Raise New Questions

FDA evaluates technological characteristics using a stepwise framework:

Do the devices share the same intended use?

Do they have the same technological characteristics?

If different, do those differences raise new questions of safety or effectiveness?

If differences raise new questions, additional data is required to address them. Materials, energy sources, control mechanisms, software behavior, and operating principles are common trigger points.

Reason #3: Predicate Recall or Market Withdrawal

The issue: Your predicate has been recalled or withdrawn, raising questions about its safety profile.

Important nuance: A recalled predicate is not automatically disqualified, but FDA will expect a clear explanation of why the recall does not undermine substantial equivalence.

Predicate status can also change during review, making this a time-sensitive risk.

This is where teams often get caught off-guard. Tracking recall status, safety communications, and post-market signals throughout development reduces surprise during review.

Reason #4: Predicate Subject to Special Controls

The issue: Your predicate is subject to device-specific special controls, and your submission does not demonstrate compliance.

Common examples include infusion pumps, glucose monitoring systems, IVDs, and certain software-based devices. If the predicate required specific performance or clinical data, FDA will typically expect comparable evidence.

Reason #5: Inconsistent Use of Multiple Predicates

The issue: Multiple predicates are used, but they support conflicting intended uses or design claims.

FDA expectation: All predicates must align with the same intended use, and the role of each predicate must be clearly defined and non-contradictory.

Reason #6: Weak or Problematic Predicate Lineage

The issue: The predicate’s own clearance history raises concerns, such as limited rationale, heavy reliance on older predicates, or post-market safety issues.

FDA is increasingly cautious about cumulative drift from well-characterized devices, sometimes referred to as predicate creep in regulatory discussions.

In practice, avoiding predicate surprises requires continuously tracking predicate clearance history, recalls, adverse events, and lineage. Centralizing this information early makes it easier to stress-test predicate strategy before FDA does.

Reason #7: Insufficient Data to Address Differences

The issue: You acknowledged technological differences but did not provide enough evidence to show they do not affect safety or effectiveness.

FDA expects data appropriate to the difference, which may include comparative bench testing, biocompatibility, software validation, shelf-life testing, or clinical data.

Key mindset shift: It is not enough to show your device is safe. You must show it does not raise different questions of safety or effectiveness compared to the predicate.

Your Response Options When FDA Challenges Your Predicate

When FDA raises concerns about your predicate strategy, there are several established paths forward. The right choice depends on how fundamental the issue is, how much new data would be required, and whether an alternative regulatory pathway makes more sense.

Option 1: Switch to a Different Predicate

When this works best:

FDA clearly indicates the current predicate is not appropriate

You have one or more backup predicates already identified

The alternative predicate is a closer match in intended use and technology

What it involves:

Identifying an alternative legally marketed predicate

Performing a gap analysis against the new predicate

Generating only the additional data needed to support substantial equivalence

Submitting an AI response that clearly explains the change

This approach is often effective when the original predicate choice was marginal but a stronger option exists.

Option 2: Strengthen the Substantial Equivalence Rationale

When this works best:

FDA agrees the predicate is relevant but questions your justification

Differences are limited and can be addressed with data or clearer explanation

What it involves:

Addressing each FDA concern point-by-point

Providing additional comparative testing or analysis

Strengthening the scientific rationale using data, standards, and literature

This is the most common recovery path when FDA’s concerns are about insufficient explanation, not fundamental mismatch.

Option 3: Withdraw and Refile with a Better Predicate

When this makes sense:

FDA’s concerns are fundamental and cannot be resolved through an AI response

A significantly better predicate exists, but would require substantial new work

The AI response would effectively become a new submission

Trade-offs:

Withdrawal avoids a formal NSE determination

Requires a new submission and restarts FDA review timelines

Often cleaner than forcing a weak predicate strategy forward

In some cases, withdrawing and refiling can be faster and less risky than prolonged AI exchanges.

Option 4: Accept NSE and Pursue an Alternative Pathway

If FDA issues a Not Substantially Equivalent (NSE) determination, the device cannot be marketed under that submission. At that point, FDA may recommend alternative pathways, depending on risk and novelty.

Common options include:

De Novo classification, for novel low- to moderate-risk devices

New 510(k) with a fundamentally different predicate strategy

PMA, for high-risk devices requiring clinical evidence

Each pathway has different evidence expectations, timelines, and resource implications.

How to Prevent Predicate Rejection Before Submission

The most effective way to deal with predicate challenges is to prevent them before FDA review begins. Teams that invest early in predicate strategy are far less likely to face AI requests or NSE determinations.

Strategy #1: Identify Backup Predicates Early

Rather than relying on a single predicate, many successful submissions evaluate multiple viable predicate options upfront.

Common approach:

Primary predicate: Best overall match for intended use and technological characteristics

Backup predicate: Acceptable alternative with similar intended use, even if technological differences are greater

Fallback predicate: Well-established device whose intended use clearly encompasses yours, with minimal uncertainty

For each option, document:

A clear comparison table

Anticipated data needed to address differences

Tradeoffs and risks

This allows you to pivot quickly if FDA questions your primary predicate.

This is where tools like Complizen are useful in practice. Evaluating multiple predicates side-by-side, including intended use, recall history, adverse events, and equivalence gaps, makes predicate strategy far more resilient before submission.

Strategy #2: Use a Pre-Submission to De-Risk Predicate Choice

FDA’s Pre-Submission program allows you to get early feedback on predicate strategy before filing a 510(k).

Common discussion topics:

Intended use and device overview

Primary and backup predicate rationale

Anticipated technological differences

Data FDA would expect to support substantial equivalence

FDA feedback at this stage often clarifies whether a predicate is viable, needs additional data, or should be avoided altogether.

Strategy #3: Validate the Predicate Thoroughly

Before committing to a predicate, confirm:

Regulatory status

Predicate is legally marketed

Clearance remains active

No unresolved safety concerns

Intended use alignment

Same anatomical site

Same patient population

Same clinical purpose

Same use environment

Technological alignment

Similar operating principle

Comparable materials and energy sources

Differences are explainable and supportable

Special controls

Identify device-specific special controls

Confirm you can meet the same requirements

Strategy #4: Build Comparative Data Proactively

Don’t wait for FDA to ask. When technological differences exist, include clear comparative data in the initial submission.

FDA expects evidence showing differences do not raise different questions of safety or effectiveness, which may include:

Comparative bench and performance testing

Biocompatibility data

Packaging or shelf-life testing

A structured comparison table makes FDA review easier and reduces back-and-forth.

This is where a structured comparison table becomes critical. Complizen’s device-to-predicate comparison tables let teams map intended use, technological characteristics, and supporting data line-by-line, so reviewers can immediately see how differences were evaluated and addressed.

Strategy #5: Monitor Your Predicate During Review

Predicate risk doesn’t end at submission. During review, predicates can be recalled, withdrawn, or subject to new safety communications.

Best practice includes:

Monitoring FDA recall and safety databases

Tracking adverse event trends

Confirming ongoing marketing status

If issues arise, coordinate early with FDA and be prepared to pivot to a backup predicate proactively rather than reactively.

The Fastest Path to Market

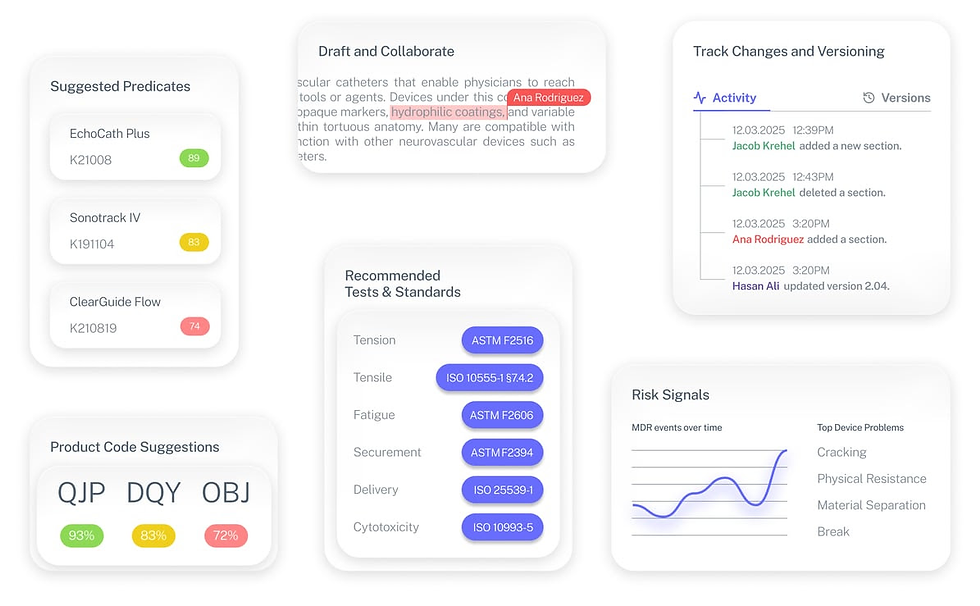

No more guesswork. Move from research to a defendable FDA strategy, faster. Backed by FDA sources. Teams report 12 hours saved weekly.

FDA Product Code Finder, find your code in minutes.

510(k) Predicate Intelligence, see likely predicates with 510(k) links.

Risk and Recalls, scan MAUDE and recall patterns.

FDA Tests and Standards, map required tests from your code.

Regulatory Strategy Workspace, pull it into a defendable plan.

👉 Start free at complizen.ai

Critical Takeaways

Predicate selection is one of the highest-risk decisions in a 510(k).

If FDA cannot agree with your predicate strategy, the review will slow, pivot, or end in an NSE determination.

Plan for backup predicates, not just a primary.

Identifying alternative predicates early gives you options if FDA challenges your first choice and reduces response time during review.

Use Pre-Submission meetings to de-risk predicate strategy.

FDA feedback before filing can clarify whether a predicate is viable and what data FDA would expect to support substantial equivalence.

Predicate challenges often surface as AI requests.

AI requests pause FDA’s review clock and typically require additional analysis or data, extending timelines depending on the scope of FDA’s concerns.

An NSE ends that submission, not necessarily your program.

After an NSE, options may include a new 510(k) with a different predicate or pursuing De Novo classification, depending on device risk and novelty.

Predicate risk continues during FDA review.

Recalls, safety communications, or new adverse event trends can emerge mid-review, so ongoing monitoring matters.

Intended use alignment is critical.

FDA evaluates whether differences in population, anatomy, clinical purpose, or environment raise different questions of safety or effectiveness, not whether devices are merely “similar.”

Technological differences require comparative evidence.

When characteristics differ, FDA expects data demonstrating those differences do not affect safety or effectiveness relative to the predicate.

Predicate quality matters more than predicate age.

A well-characterized predicate with clear intended use and robust clearance rationale is often stronger than a newer but less comparable device.

Withdrawal can be a strategic decision.

When FDA concerns are fundamental and an AI response would require substantial rework, withdrawing and refiling with a stronger predicate may be the lower-risk path.